Introduction:

As a crucial learning and developing process, group discussion enables students to improve oral communicative competence (Albertertson, 2020) and stimulate their critical thinking skills based on related topics. However, the issue of student reticence and limited engagement in group discussions has been extensively researched and consistently acknowledged on a global scale (Liu, 2009 ), and even advanced-proficiency students may remain silent during discussions (Albertertson, 2020). As a transnational university, XJTLU shifted all its English for Academic Purposes (EAP) classes to an online format in Semester 2, 2022 because of the pandemic situation. Compared with onsite discussion, a notable decrease in engagement and an increase in student silence were detected when they are put in online breakout rooms for discussions. Zapata-Cuervo et al. (2021) state that mandatory online learning can raise concerns about student disengagement, potentially impacting the quality of online education.

Therefore, it is valuable to understand the reasons behind student reticence in online discussions and find solutions to develop an effective learning environment. Drawing from Chertow & Rubins' (1969) pedagogic theory, the effectiveness of online discussions is influenced by three basic components: Group, Leadership, and Content. This action research aims to explore whether assigning leader and group member roles can enhance online discussions by analyzing the underlying causes of students’ limited engagement. The aspect of how 'Contents' contribute to effective discussions, as per this theory, remains a subject for future research.

This study addresses two key research questions:

- What are the reasons behind less engagement in online group discussions?

- What leadership roles and member roles are valuable for boosting active discussion participation in online learning environments?

The objective of this study is to offer insights into boosting students’ participation in group discussion by assigning leader and member roles by examining the evidence, in order to facilitate students’ learning and English speaking in an online learning environment.

Literature Review

A multitude of reasons contribute to students’ less engagement and silence in group discussions. Jordan (1997) and Kim et al (2016) believe that individual characteristics, such as introversion, can lead to reticence. Additionally, a lack of confidence in English proficiency often deters students from volunteering their opinions due to the fear of making mistakes and 'losing face' (Campbell, 2007). Furthermore, students with poor motivation tend to be less engaged in discussions (Jordan, 1997). Other factors, including teacher interaction styles (Morita, 2004), the closeness among classmates, and classroom size (Sasaki & Ortlieb, 2017), prior experiences of speaking English (Osterman, 2014), and the overall classroom environment (Banks, 2016), also impact students' participation in group discussions.

Chertow&Rubins (1969) divided group discussions into three components: Leardership, Group, and Contents. These components collaboratively influence the learning situation of the discussion, with each functioning in dynamic interrelationships rather than in isolation. While prior research has confirmed the positive impact of leadership and member roles in effective discussion groups, few studies have delved into identifying the specific roles of leaders and members that prove valuable in addressing the issue of group silence.

Methodology

The participants were students from four EAP105 classes at XJTLU, currently in their second semester of the second year at the university. At the first stage, 40 online questionnaires including the question types of ‘Likert Scale’ and ‘Multiple Choices’ were sent to students selected randomly, and 28 of them have been successfully collected. The subsequent stage involved a 2-week intervention and observation period. Before making students enter into breakout rooms and have discussions in BBB (online class delivery platform of XJTLU) live sessions, a group leader with different responsibilities or other roles were assigned. During this phase, the performance and engagement of students in breakout rooms were closely observed and evaluated. At last, 10 volunteers were selected from the above students to take online individual interviews.

Results and Discussion

Theme 1

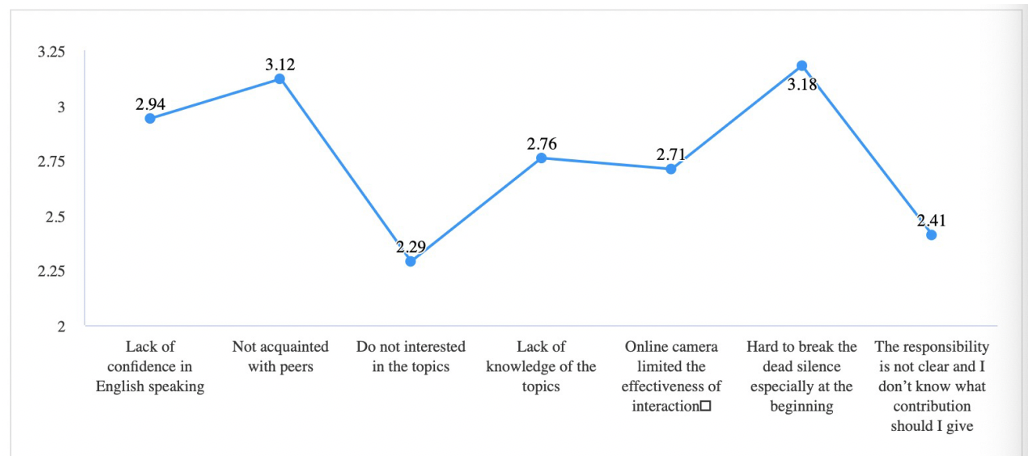

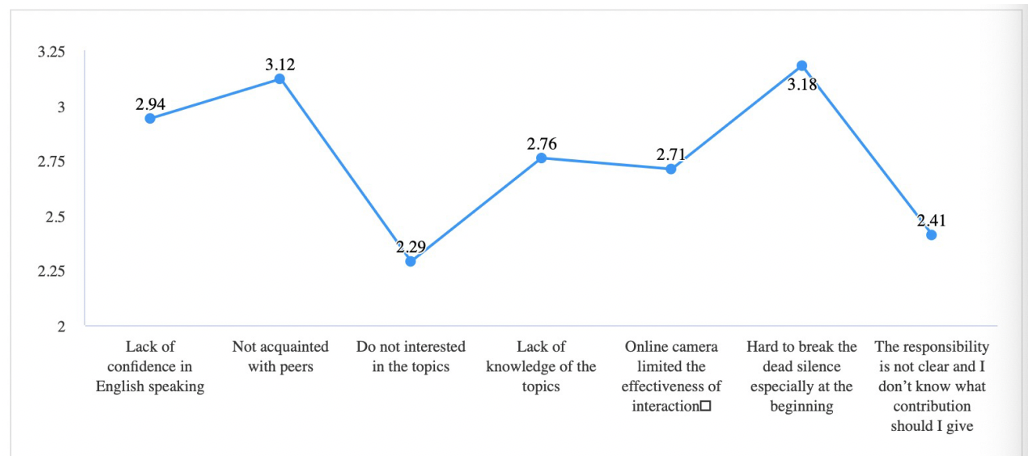

Theme 1 focuses on the factors that particularly restrict students’ engagement in an online learning environment. Students were tasked with rating these factors on a scale of 5 points (extremely true for them) to 1 point (not at all for them). Figure 1 illustrates the findings, where 'hard to break the dead silence, especially at the beginning' emerged as the most significant reason, with an average rating of 3.18. Following closely was 'not acquainted with peers' with an average rating of 3.12. It's noteworthy that the reason 'not clear responsibilities and contribution' received a lower rating of 2.14. This could be attributed to the fact that general member roles, such as initiating, documenting, or reporting, had been assigned since Week 1 of the semester. Consequently, students were already clear about their general responsibilities. Adding qualitative insights, Student A expressed, “Starting a discussion staring at the screen without seeing others' faces is especially challenging, and it makes me feel embarrassed if I receive no response after expressing myself.” Student B expanded on this by noting, “Sometimes, the discussion falls into silence initially because nobody wants to be the first one; it seems that most students prefer to wait.”

Figure 1: Rate the reasons limiting your participation in online discussion from 5 (extremely true) to 1 (not at all).

Theme 2

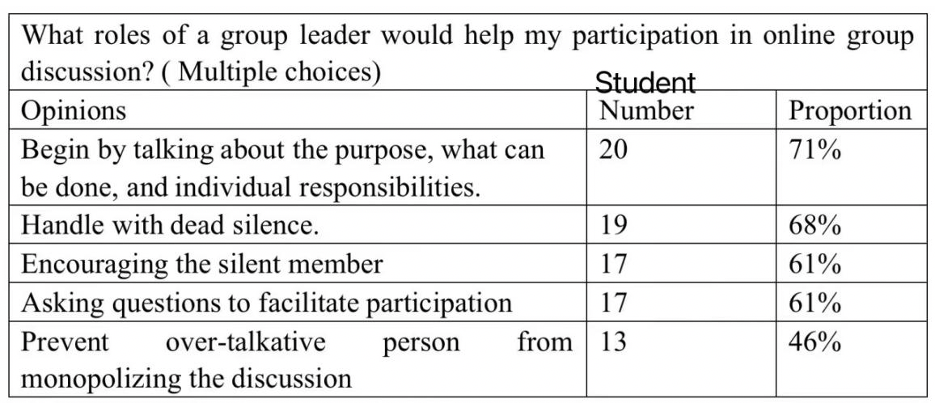

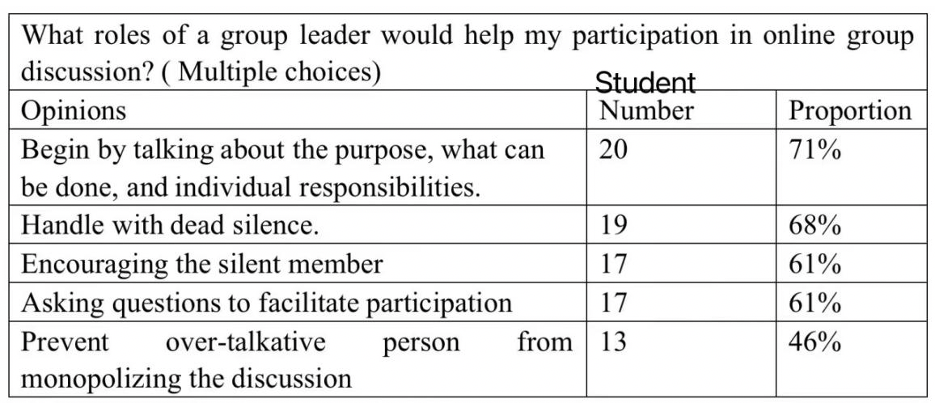

Theme 2 analyzes the positive roles of leaders and group members in discussions aimed at stimulating participation. In the multiple choices questions about regarding helpful leader roles, 20 students voted “beginning the discussion by introducing the purpose and responsibilities of members” as the most desirable role, ranking it first. Another 19 students considered "handling dead silence" as a crucial responsibility for a group leader (Figure 2). During the 2-week online classroom observation, a leader with these responsibilities was assigned to each group before students entered breakout rooms, resulting in improved engagement across all groups.

To be more specific, there was no longer unnatural waiting time at the first beginning, because the group leader initiated the discussion by introducing the purpose and assigning the first speaker. Shy or quiet students were encouraged to participate naturally, with nearly all students contributing during the discussion. Subsequent interviews supported this evidence. Student C provided an example, stating, "The group leader saved the discussion from dead silence by calling members' names one by one and asking for their opinions when the team was quiet." The evidence suggests that assigning a leader responsible for organizing self-introductions, task delegation, breaking the initial silence, and encouraging silent members is crucial to ensuring equal participation.

However, according to Chertow&Rubins (1969), the leadership role should be shared by group members in an effective discussion to avoid monopoly. Therefore, different member roles are also necessary for an effective and efficient discussion. The data from questionnaire shows that 71% of students valued the importance of “Introducing new angles or aspects of topic for consideration” from the members, with Student E explaining, "When we have similar opinions and reach an agreement after a short communication, we tend to stay silent. But if a member provides a new perspective, it is easy for us to have a new round of discussion ”. Another member role desired by 57% of participants is “Seeking clarification of unclear ideas”. This is because interaction is the key to continue the discussion, and if someone's idea is unclear, it becomes challenging for other members to respond, resulting in silence. Other roles such as “seeking further opinions”, “bringing discussion back to point” and “summarizing” also play crucial roles in facilitating effective discussions among group members (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Conclusion

Based on the theory proposed by Chertow&Rubins (1969), this action research investigates the causes of students’ less engagement in group discussions. It specifically explores the roles of leaders and members that can actively involve students in discussions, with the aim of providing equal opportunities for learners through intervention.

However, acknowledging the limitations of this action research, it is essential to highlight the brief intervention period and the insufficient consideration given to the delegation of member roles among different students. Chertow & Rubins (1969) emphasize the need to distinguish member roles from personalities, recognizing that students assume different roles in a group depending on the activity. Due to the constraints of online teaching, a comprehensive understanding of diverse student characteristics may be lacking, potentially leading to the improper delegation of roles. This also provides field for future research, together with ‘Content’, which is also crucial determiner for an effective discussion (Chertow & Rubins, 1969).

Reference

Albertson, B. P. (2020). Promoting Japanese university students’ participation in English classroom discussions: Towards a culturally-informed, bottom-up approach. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 45-66.

Banks, S. (2016). Behind Japanese students’ silence in English classrooms. Accents Asia, 8(2), 54-75.

Campbell, N. (2007). Business Communication Quarterly. Vol. 70 Issue 1, p37-43. 7p. DOI: 10.1177/108056990707000105.

Chertow, D.S and Rubins, S. G (1969). Leading Group Discussion: A Discussion Leader's Guide, Syracus University, N.Y. Publications Program in Continuing Education.

Jordan, R. R. 1997. English for Academic Purposes: A Guide and Resource Book for Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, S. et al . (2016). Ways to promote the classroom participation of international students by understanding the silence of Japanese university students. Journal of International Students, 6(2), 431-450.

Liu, M. (2009). Reticence and Anxiety in Oral English Lessons. Bern: Peter Lang.

Morita, N. (2004). Negotiating participation and identity in second language academic communities. TESOL Quarterly, 38(4), 573-603.

Osterman, G. L. (2014). Experiences of Japanese university students’ willingness to speak English in class: A multiple case study. SAGE Open, 4(3). doi: 10.1177/2158244014543779

Sasaki, Y., & Ortlieb, E. (2017). Investigating why Japanese students remain silent in Australian university classrooms: The influences of culture and identity. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 27(1), 85-98.

Zapata-Cuervo, N et al. (2021). Students’ psychological perceptions toward online learning engagement and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative analysis of students in three different countries. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 1-15