Abstract

This paper examines the implementation and effects of gamification in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) instruction, specifically targeting pre-intermediate level students in EAP classrooms. Existing empirical research and theoretical frameworks related to gamification are reviewed, highlighting the potential of gamification for improving student motivation and engagement. The paper introduces the mechanisms and elements underpinning the design of gamified language learning experiences. Furthermore, the paper delves into the use of specific technologies, such as Gimkit, Genially and PPT games, as well as their integration into EAP instructional practices. Practical implications and recommendations for teachers seeking to implement gamification strategies in ESL classrooms are also discussed, including the facilitation of group activities, the incorporation of hidden tasks and the active engagement of teachers within the gamified learning environment.

Key words: Gamification, Educational Technology, Student Engagement, Second language learning, Learning motivation.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Improving students’ engagement and motivation in class has been considered as a crucial and challenging task for ESL teachers. It can be an even more serious issues in EAP classes where Chinese students frequently exhibit reticence in participating in specific learning tasks, such as group discussions. Moreover, the insufficiency of instructional materials and learning tasks in captivating and sustaining students’ attention presents a formidable challenge. Mundane and repetitive exercises, notably vocabulary drills, often fail to engross students. As a response to these challenges, empirical research endeavors have been undertaken to investigate potential approaches aimed at bolstering students’ motivation in English language learning. Educators and practitioners have undertaken concerted efforts to devise interactive and highly engaging pedagogical methods. Among the prominent strategies, the incorporation of gamification has emerged.

Landers et al. (2017) defined gamification as the integration of diverse gaming elements, including badges, leaderboards and points within non-game contexts, and its objective is to foster a game-like environment. Kapp (2012) asserts that gamification endeavors to enhance learning engagement and foster students’ learning autonomy by establishing a more immersive and interactive learning environment. An array of studies has indicated that gamification can catalyze the learning process by facilitating and stimulating student participation in learning tasks, mitigating the impact of frustration and other adverse emotions (Deterding et al, 2011; Kapp, 2012; Bicen and Kocakoyun, 2018). Within the ESL context, empirical investigations have affirmed that the integration of gamification in ESL classrooms can confer benefits to learners by alleviating learning anxiety, bolstering learning performance, and cultivating learning autonomy (Barcomb and Cardoso, 2020; Hung, 2018). This paper aims to expound upon several gamification technologies and practices within the teaching context of Y1 EAP classes. Additionally, it will provide insights into the mechanics and practical recommendations for prospective practitioners.

1.2 Mechanisms and Framework

Several mechanisms and elements are investigated by practitioners and literatures in designing gamified language learning classes. Chen and Chun (2008) mentioned that using appropriate incentive mechanisms can strengthen learning interest and motivation through effectively enhancing their enjoyment and creating immersive experiences of playing games.

Acquah and Katz (2020) identified six fundamental game characteristics in language learning games, encompassing user-friendliness, difficulty, incentives and assessment, individual autonomy, objective-driven design, and interactive features. In a similar vein, Xu et al. (2020) proposed enhancing game design through the incorporation of gaming elements such as unpredictability, empowerment and adaptive complexities, which were observed to be underutilized in the studies analyzed. Furthermore, Govender and Arnedo-Moreno (2021) scrutinized game design components, revealing that prevalent components include assessment, theme, scoring, storyline and progression levels.

One main mechanic I refer to during the design of the games is the Octalysis Framework for Gamification created by Yu-kai Chou, a prominent gamification expert. It’s widely used to design and analyze gamified experiences. The framework consists of eight core drives that motivate human behavior. It provides a systematic approach to understanding and implementing gamification in various contexts (Chou 2019).

• Epic meaning and calling: Engaging individuals in tasks that they perceive as being more significant than themselves or feeling chosen to undertake a specific mission.

• Development and accomplishment: Stimulating individuals’ innate drive to progress, enhance skills, achieve mastery and ultimately conquer challenges.

• Empowerment of creativity and feedback: Encouraging individuals to generate new ideas, experiment with different combinations, and providing opportunities to receive feedback on their creations and respond accordingly.

• Ownership and possession: Instilling a sense of ownership or control, fostering motivation to acquire more or improve what they already possess.

• Social influence and relatedness: Encompassing social elements that enable individuals to connect, compete, or establish connections with others, places, things, or events.

• Scarcity and impatience: Structuring situations to make items scarce, unique and immediately obtainable to motivate individuals to acquire them.

• Unpredictability and curiosity: Cultivating individuals’ curiosity about what will happen next.

• Loss and avoidance: Prompting individuals to act in order to prevent missing opportunities or experiencing negative occurrences.

According to Chou (2019), the Octalysis gamification framework categorizes three core drives, comprising “development and accomplishment”, “ownership and possession”, and “scarcity and impatience”, as extrinsic motivators, while other three core drives, including “empowerment of creativity and feedback”, “social influence and relatedness”, and “unpredictability and curiosity”, are considered intrinsic motivators.

2. Technology

2.1 Gimkit

Gimkit is an educational platform that offers interactive learning games and tools for students and teachers. It provides a fun and engaging way for students to review and reinforce their learning through a variety of game-based activities. Teachers can create custom quizzes, flashcards and other study materials to support their students’ learning goals. Gimkit can be used as a tool to effectively help students with vocabulary learning and reviewing. Undoubtedly, language learners face considerable challenges in acquiring vocabulary, as evidenced by research (Jia et al, 2012). Furthermore, the issue of forgetting vocabulary poses a significant concern for language learners, as indicated by studies (Chen and Chung, 2008). Research has suggested that these difficulties may be linked to a deficiency in motivation (Hasegawa et al, 2015). With the help of Gimkit, students are highly motivated to complete vocabulary learning tasks.

Firstly, as a teacher, you can create a new game by setting up a quiz or study set. Then, you can customize various settings such as the question format, point system and game duration to suit your learning objectives. Once the game is set up, students can join and start playing using their devices.

2.2 Genially

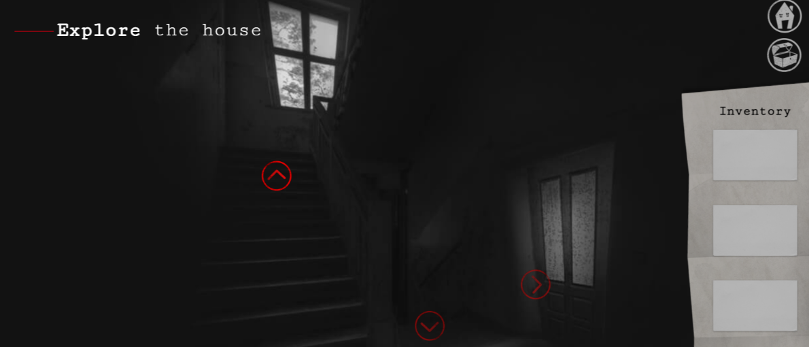

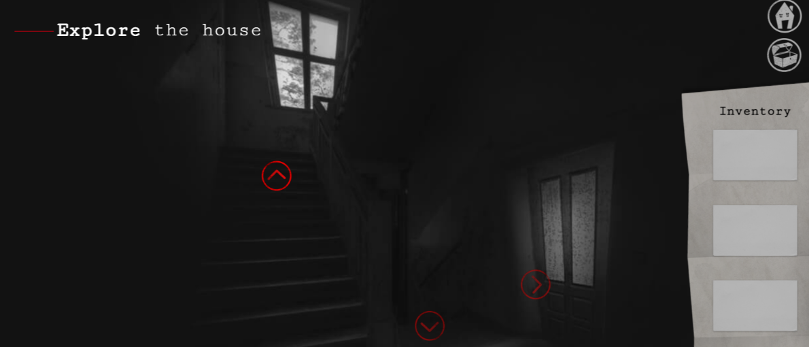

Genially is an online platform that allows users to create interactive and multimedia-rich educational content, presentations, infographics and other visual materials. It offers a variety of templates and design elements to help users craft engaging and dynamic digital resources. Genially can be utilized by educators and students to create visually appealing and interactive learning materials, making it a popular choice for modern educational settings. The templates make it easy and efficient to create digital games during the class, such as board games, tic-tac-toe, connected four and escape room games. Two templates are frequently used in my classes. The first one is an escape room game (see Figure 1). Students need to complete learning tasks in order to make a movement in the game which can help them escape from this horror house in the end. To make it engaging, a health point system is introduced in this game. Under this system, students lose health points for incorrect responses, with potential punishment if they exhaust their allotted health points. This system significantly motivates students aligning with the drive of loss and avoidance, as students try very hard to answer questions in order to avoid losing health points.

Fig 1. Horror Escape Room in Genially.

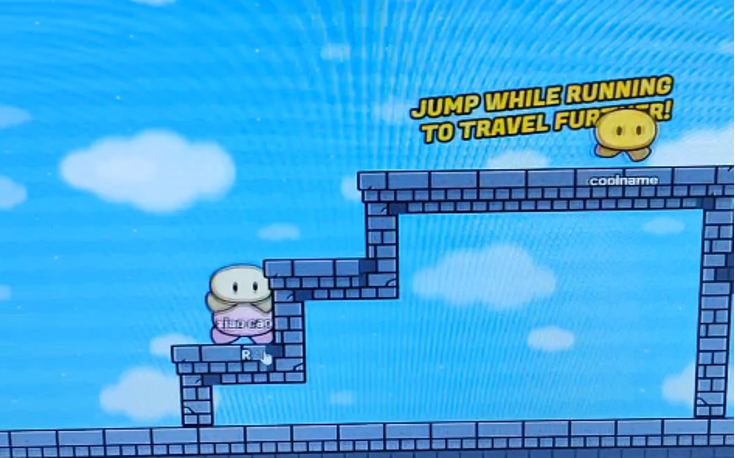

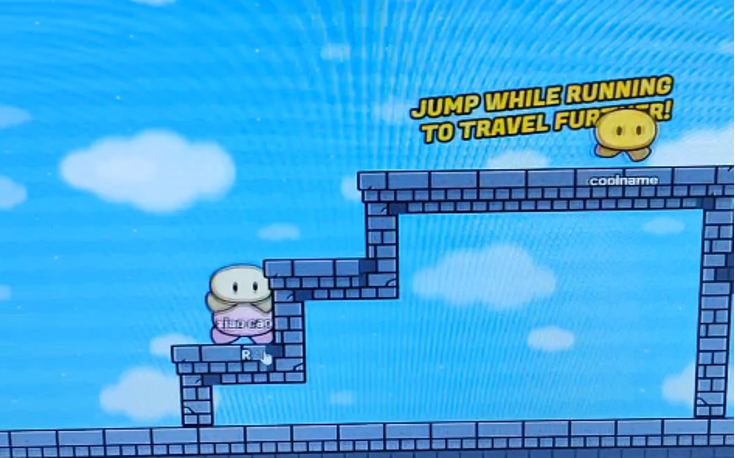

Another template utilized is a digital board game (see Figure 2) designed to simulate the experience of a traditional board game within a digital format. Students are divided into four groups and are granted the opportunity to roll the dice upon completion of learning tasks. The team that makes the most progress emerges as the victor, fostering a sense of accomplishment and incentivizing students to persist in answering questions in order to earn the chance to roll the dice, thereby aligning with the core drive of Development and Accomplishment. An interesting feature of this game is the inclusion of hidden tasks upon reaching a designated spot, requiring students to fulfill these additional tasks to remain in that position. This design not only infuses the activity with enjoyment but also spurs students to persist, driven by their curiosity about the hidden tasks behind the spot and the potential for additional rewards, thus reflecting the core drive of Unpredictability and Curiosity.

Fig 2 Board Game in Genially

2.3 PPT games

Many educators are familiar with leveraging PowerPoint (PPT) as a valuable tool for gamifying instructional activities within the classroom setting. In this context, I will detail the approach taken to gamify my class through the utilization of PPT games. As depicted in Figure 3, a frequently employed game format is the “Bomb game”, a popular choice in ESL classes. This game involves populating the slides with various special events. Students are required to complete learning tasks, after which they can select an option (letter, number, etc.) that corresponds to hidden tasks, bonuses, or a potential “bomb”. This design aligns with the core drive of Unpredictability and curiosity, motivating students to persist in their efforts to uncover the hidden tasks associated with each designated option.

Fig 3 Pokemon Bomb game

2.4 Super Power card

The implementation of the “Super Power card” represents a pedagogical approach utilized to incentivize positive behaviors in the classroom, such as the timely submission of coursework or the proficient completion of asynchronous learning tasks. Students who possess a Super Power card can have competitive advantages in classroom games, including the ability to acquire points from another team or double the points they have earned. These cards are generated through the website https://cardconjurer.com/ and feature images created through artificial intelligence, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Fig 4 Super Power Card

3. Teaching Practice

In this chapter, I will delineate the utilization of these technologies within the context of an EAP class involving pre-intermediate level students. The instructional session encompasses vocabulary review, listening tasks and discussion exercises.

Grouping

At the beginning of the class, students are divided into four groups and tasked with devising a team name, written on the whiteboard at their desks. This initial group discussion serves as an ice-breaking activity, fostering student engagement and teamwork. To facilitate the process, a predefined naming convention is introduced, such as the requirement for the team name to include a shape, a color, and an animal (e.g., “a triangle yellow raccoon”), thereby empowering students to exercise creativity without fear of committing errors. This activity aligns with the core drive of Empowerment of creativity and feedback, fostering an environment where there are no definitive right or wrong answers, thereby encouraging students to express themselves with confidence.

Introduction of the game setting

Subsequently, the instructor introduces a board game designed through the Genially platform as the central activity of the class. In this game, students collaborate in teams to provide speedy, accurate responses to learning tasks. The first team giving the correct answer will be granted the opportunity to roll the dice and advance through the game board. By employing this game format, the focal point of the class transitions from mere learning to a competitive element, creating a sense of purpose and motivation among students, thereby resonating with the core drive of Epic meaning and calling.

Vocabulary task

Following the game introduction, students engage in the first learning task, which involves vocabulary matching. Here, instead of traditional workbook exercises, students are tasked with completing the activity on the Gimkit platform using the “don’t look down” game format (see Figure 5). This game entails students “jumping” within the game, with the highest performer being declared the winner. As each move within the game consumes energy, students need to answer questions correctly to gain energy to keep on moving. Post-game, both students and instructors engage in a review of performance data and analytics, identification of improvement areas and tracking of progress (see Figure 6). The top-performing student is rewarded with the opportunity for their team to roll the dice. Furthermore, the victor is also rewarded with the privilege of selecting a Super Power card, which confers additional competitive advantages, such as an extra dice roll or the ability to freeze other teams, further motivating student engagement and participation.

Fig 5 “Don’t look down” in Gimkit

Fig 6 Student overview in Gimkit

Listening task

Next, students are tasked with completing a listening exercise. Just like the vocabulary task, the team that provides the correct response can earn the opportunity to roll the dice and advance their position within the game. However, in order to make the game more interesting and engaging, specific spots are incorporated into the board. Upon landing on one of these designated spaces, the team is required to fulfill a hidden task to maintain their position, failing which they revert to their starting point.

Speaking task

Finally, students are called upon to partake in a follow-up discussion. Engaging in classroom discussions can often be a challenge for many students. To encourage active participation, the team that exhibits the most vocal engagement is rewarded with a Super Power card. Additionally, following the discussion, each team takes turns presenting their discourse to the class, after which all team members are permitted to roll the dice and advance their positions. During the game, students who have the Super Power card can use it to help their team to win or prevent other teams to go further.

4. Suggestions

4.1 The design of hidden tasks

The hidden tasks are the key to the success of this game as they can reward students with extra bonuses such as rolling the dice one more round; and surprise students with a punishment such as going back three steps; or even entertain the class such as singing a song in order to stay here. Here are some recommended special tasks:

1. Bonus: students can gain extra points for one round or change their points with another team. This will motivate them to complete the learning tasks first place as they want to gain more. It echoes with the drive of Development and accomplishment.

2. Pop quiz: students need to answer some simple questions such as the deadline of the Writing Coursework or listing core task requirements of the Speaking Coursework. This can be used to review some knowledge.

3. Speaking task: one of the students needs to speak for 1 minute on a given topic in order to gain extra points.

4. Fun activities: students need to perform some fun activities such as singing a song or reading an English tongue twister. This will add more fun to the class and keep students interested.

The guiding principle behind the design of these special tasks is for them to fulfill at least one of the following purposes: reward, punishment, education, or entertainment, thereby reflecting the drives for unpredictability and curiosity; ownership and possession; and loss and avoidance.

4.2 Teachers’ involvement

The active engagement of teachers within the gamified learning environment is integral to the success of game design, as students are more inclined to participate when the teacher is actively involved. Here are three instances of how teachers engage within the gamified learning environment:

1. Super Power card. One of the super power students can win is the ability to seek the teacher’s assistance. Through this card, the teacher can aid the team in completing learning or hidden tasks. It can also resonate as an enjoyable experience when the teacher is invited to complete the hidden tasks, such as singing or dancing.

2. Using the teacher as a story line to play PPT game. One setting of the escape room game played in my class is that the teacher is kidnapped and students need to finish all the learning tasks to rescue him. This reflects the drive of Epic meaning and calling as they are being more significant than themselves through saving the teacher’s life.

3. Rewarding the students. Teachers may provide students with personalized incentives, such as the promise to buy the game winner a cup of coffee in the next class, serving to motivate students and foster a closer rapport.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has explored the application of gamification in the context of EAP, with a focus on addressing Chinese students’ reticence and motivation in language learning tasks. The integration of gamification elements has been identified as a potentially effective approach to enhancing student engagement and motivation in English language learning. The adoption of gamification practices in language learning classrooms has been shown to alleviate learning anxiety, bolster learning performance and cultivate learning autonomy.

Moving forward, future studies in this area could delve deeper into the efficacy of specific gamification elements and mechanics in different language learning contexts, including the impact of incentive mechanisms, game characteristics, and game design components on student motivation and engagement. Additionally, further research is warranted to explore the potential of gamification technologies, such as Gimkit and Genially, in enhancing vocabulary acquisition, listening tasks, and discussions within language learning classrooms. Moreover, the implementation of game-based practices, such as PPT games and the use of Super Power cards, presents opportunities for further investigation. Future studies may seek to examine the effectiveness of these game-based strategies in fostering active participation and motivation among language learners.

In summary, the study of gamification in language learning continues to offer promising avenues for enhancing student motivation, engagement, and language acquisition. By leveraging gamification elements and technologies, educators can create dynamic and immersive learning experiences that cater to the diverse needs and learning styles of language learners, ultimately fostering a more interactive and engaging language learning environment.

Reference list

Acquah, E. O., and Katz, H. T. (2020). Digital game-based L2 learning outcomes for primary through high-school students: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 143, doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103667

Barcomb, M., and Cardoso, W. (2020). Rock or lock? Gamifying an online course management system for pronunciation instruction: Focus on English/r/and/l/. CALICO J. 37, 127–147. doi: 10.1558/cj.36996

Bicen, H., and Kocakoyun, S. (2018). Perceptions of students for gamification approach: Kahoot as a case study. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 13, 72–93. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v13i02.7467

Chen, C. M., and Chung, C. J. (2008). Personalized mobile English vocabulary learning system based on item response theory and learning memory cycle. Computers & Education, 51(2), 624-645.

Chou, Y. K. (2019). Actionable gamification: Beyond points, badges, and leaderboards. Packt Publishing Ltd.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011). “From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining” gamification,” in Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, (New York, NY: ACM). doi: 10.1145/2181037.2181040

Govender, T., and Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2021). An analysis of game design elements used in digital game-based language learning. Sustainability, 13(12), 6679.

Hasegawa, T., Koshino, M., Ban, H. (2015). An English vocabulary learning support system for the learner’s sustainable motivation. Springer Plus, 4(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.11- 86/s40064-015-0792-2

Hung, H. (2018). Gamifying the flipped classroom using game-based learning materials. ELT J. 72, 296–308. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccx055

Jia, J., Chen, Y., Ding, Z., and Ruan, M. (2012). Effects of a vocabulary acquisition and assessment system on students’ performance in a blended learning class for English subject. Computers & Education, 58(1), 63-76. doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.002

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. doi: 10.1145/2207270.2211316

Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., and Callan, R. C. (2017). Gamification of task performance with leaderboards: A goal setting experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 71, 508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.008

Lee, J. J., & Hammer, J. (2011). Gamification in education: What, how, why bother? Academic exchange quarterly, 15(2), 146.

Xu, Z., Chen, Z., Eutsler, L., Geng, Z., & Kogut, A. (2020). A scoping review of digital game-based technology on English language learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 877-904.

Author biography

Xiao Cao is an associate language lecturer at the School of Languages, Xi'an Jiaotong- Liverpool University, China. His research interests are innovative pedagogical approaches to enhance students' learning experiences and the integration of gamification into language teaching.

Xiao.Cao@xjtlu.edu.cn